You eat lunch, feel fine for about 20 minutes, then your eyelids get heavy. An hour later you’re poking around the pantry, hunting for something sweet, even though you “just ate.” Or maybe your rings feel tight, your face looks a bit puffy, and you can’t quite put your finger on why.

That after-meal slump can have a few causes, but one big piece is postprandial inflammation, a temporary rise in inflammatory stress signals after eating. In small doses, this response is normal. Your body is processing food, moving nutrients into cells, and cleaning up the byproducts.

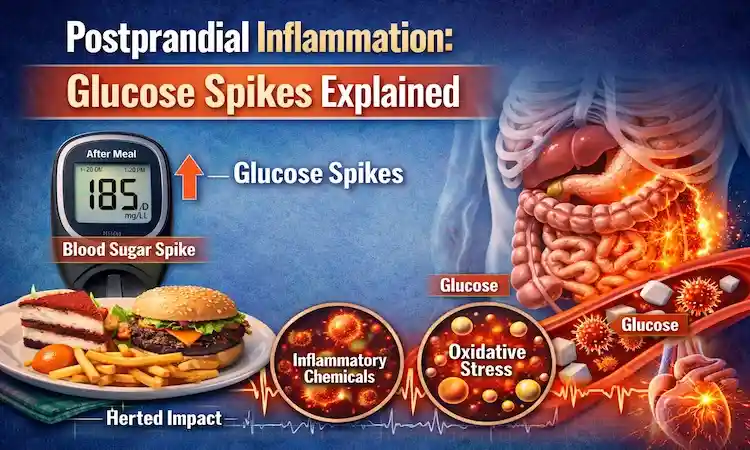

The problem starts when the after-meal response gets loud and frequent. Big, fast glucose spikes can act like an alarm bell, triggering oxidative stress, irritating blood vessels, and pushing insulin to work overtime, even in people without diabetes. Research reviews on post-meal metabolism and low-grade inflammation describe how common these short-term shifts can be in everyday life, not just in lab settings (see this review on postprandial metabolism and inflammation).

Here’s what causes spikes, what’s happening inside your body, how to spot patterns (including CGM glucose spikes), and how to smooth the curve without extreme dieting.

What happens in your body after you eat, and why glucose rises

After you eat, your digestive system breaks carbs into glucose, a simple fuel your blood carries to your tissues. As glucose enters the bloodstream, the pancreas releases insulin. Insulin is the “key” that helps glucose move from blood into muscle, liver, and fat cells.

In a steady, healthy response, blood sugar rises, insulin rises, cells take in fuel, and glucose returns closer to baseline within a few hours. Your liver also plays traffic cop, storing some glucose as glycogen and releasing it later when you need energy. Your gut hormones help, too, telling the pancreas how much insulin to release and telling your brain you’re full.

This whole system is meant to handle meals. It becomes more of an issue when the rise is too high, too fast, or happens over and over across the day. Then the body reads the surge as stress. You might not “feel inflamed,” but internally there can be more oxidative stress after meals, more irritation in the vessel lining, and more inflammatory signaling than you want as a daily routine.

The normal post-meal “rise and fall” vs a true glucose spike

Think of a normal glucose response like a gentle hill. It goes up, it comes down, and you keep walking.

A glucose spike is more like a steep roller coaster: a sharp climb followed by a faster drop. That drop can be the moment you feel shaky, hungry, moody, or foggy, because your body is trying to pull glucose out of the blood quickly. Over a full day, the up-and-down pattern is called glycemic variability.

Spikes can happen with or without diabetes. People with diabetes often see bigger and longer spikes, but research suggests that frequent large swings can matter for many people because they may stress blood vessels and increase inflammatory signals. A review discussing why post-meal glucose spikes can be harmful highlights how short, repeated bursts may contribute to cardiovascular risk over time (see this review on postprandial glucose spikes).

Why some meals spike more than others

Meals don’t all behave the same, even when calories match. A few drivers make spikes more likely:

Refined carbs digest fast (think white bread, pastries, many cereals). Liquid sugar hits even faster because there’s less chewing, less fiber, and quick stomach emptying. Portion size matters, too. A “healthy” food can still spike you if the carb load is large for your body at that moment.

What’s missing from the plate is just as important. Protein, fiber, and fat slow digestion and glucose entry into the bloodstream. Eating quickly can also raise the peak, since your gut gets a sudden flood of fuel.

A simple swap shows the idea. Juice plus a pastry often creates a fast rise and a later crash. Eggs plus berries plus a handful of nuts (similar calories for some people) tends to create a smaller bump because digestion is slower and the carb dose is more fiber-rich. Personal biology plays a role as well. A Stanford Medicine report explains that people can have very different glucose responses to the same carbohydrate foods, which is one reason one-size advice falls short (see Stanford’s report on blood sugar responses to carbs).

How glucose spikes can trigger postprandial inflammation

A big glucose surge doesn’t just raise a number on a screen. It changes chemistry in real time.

When glucose rises quickly, cells take in more fuel than they can smoothly burn. That mismatch can increase reactive oxygen species, sometimes described as metabolic “sparks.” Your body has antioxidant systems to neutralize them, but sharp, repeated spikes can tilt the balance toward more oxidative stress after meals.

This matters because oxidative stress can activate inflammatory messengers. It can also affect the endothelium, the thin lining inside blood vessels that helps arteries relax and keeps blood flowing smoothly. When the endothelium is irritated, vessels may stiffen for a while and become more “sticky,” which is not what you want happening several times a day.

At the same time, your insulin response has to scale up. Bigger spikes usually require more insulin to bring glucose down. Over time, that can nudge some people toward insulin resistance (a spectrum, not a switch), where cells don’t respond as well, so the pancreas has to push even harder.

None of this means one spike ruins your health. The concern is the pattern: frequent, high swings paired with low activity, poor sleep, and chronic stress can make postprandial inflammation more common.

Oxidative stress after meals, the “spark” that starts the trouble

Oxidative stress is what happens when reactive particles outpace your body’s ability to calm them down. Picture a kitchen: a few sparks while cooking are normal, but a grease flare-up every day starts damaging surfaces.

A rapid glucose rise can increase those sparks. When that happens, cells may turn on signaling pathways that increase inflammatory markers and reduce nitric oxide availability (nitric oxide helps blood vessels relax). Reviews on post-prandial oxidative stress describe how the “nutritional load” of a meal, including rapid carbohydrate absorption, can shape this short-term oxidative response (see Nutritional load and post-prandial oxidative stress).

The key idea is dose and frequency. If most meals create moderate rises, the body handles it. If many meals create steep peaks, the oxidative signals can stack up.

What blood vessels have to do with it (endothelial dysfunction in plain English)

The endothelium is a one-cell-thick lining inside your arteries. It’s like Teflon for your bloodstream: it helps vessels widen when needed, discourages unwanted clotting, and keeps immune cells from sticking around.

After large glucose spikes, studies show the endothelium can function worse for a period of time. Blood vessels may not dilate as well, and inflammatory and oxidative signals may rise together. This temporary impairment is often described as endothelial dysfunction, and it’s one reason postprandial inflammation is not just a weight issue.

If you want to see what scientists measure in these studies, flow-mediated dilation (a way to test how well an artery expands) is commonly used. A PubMed-listed paper on postprandial hyperglycemia and vascular endothelial function describes how a high-sugar challenge can reduce vascular function during the post-meal window (see postprandial hyperglycemia and endothelial function).

Insulin’s role, when the post-meal insulin response is working harder than it should

Insulin isn’t the villain. It’s a necessary hormone that lets you use carbs, build muscle, and store energy. The issue is the workload.

When glucose shoots up fast, the body often answers with a stronger post-meal insulin response. That can bring glucose down quickly, which sounds good until the drop feels like a crash. Many people then reach for more carbs, starting a loop of spike, drop, snack, repeat.

Insulin resistance fits here as a gradual change: over time, some cells respond less to insulin’s “knock,” so the pancreas knocks louder. You can be on that path years before a lab test crosses a diagnostic line. Smoother glucose curves can reduce how often the system needs to hit the gas and the brakes in the same afternoon.

How to tell if your meals are causing spikes (without obsessing)

You don’t need to treat eating like a science fair project. The goal is pattern recognition, not perfection.

Start with context. Stress hormones can raise glucose. Poor sleep can make you more insulin resistant the next day. Illness, menstrual cycle changes, and certain medications can all shift your response. So can a hard workout. When your body feels “off,” your glucose curve may look different even with the same meal.

A simple way to learn is to pick one meal you eat often and notice what happens after it. How’s your energy at 30 minutes, 90 minutes, and 3 hours? Do you feel steady, or do you feel pulled toward snacks?

Clues your body gives you after eating

These aren’t diagnostic signs, but they can hint at a sharp rise and fall:

- Sudden sleepiness within 30 to 60 minutes

- Strong cravings 1 to 3 hours later (often for sweets)

- Shaky, “hangry” feelings, especially if you go longer between meals

- Brain fog or trouble focusing

- Headaches for some people, especially after sugary drinks

If these happen most days, it’s worth experimenting with meal makeup and timing, and talking with a clinician if symptoms are intense.

Using a CGM to learn your personal triggers (and what to look for)

A continuous glucose monitor (CGM) tracks glucose through the day and night using a small sensor. It can be useful for curious learners, athletes dialing in fueling, people with a family history of diabetes, and anyone trying to understand their own glycemic variability.

The best way to use a CGM is to compare repeats, not single readings. Eat the same breakfast on two different days and see if sleep, stress, or a post-meal walk changes the peak. Look for your biggest “usual suspects,” which often include sweet drinks, dessert on an empty stomach, and large refined-carb portions without protein.

Also remember: CGM data is information, not a grade. Treat it like a weather app. It helps you plan, but you still live your life.

Simple, realistic ways to smooth glucose spikes and calm post-meal inflammation

You don’t need to cut all carbs to reduce postprandial inflammation. You need fewer steep peaks and fewer hard crashes. That usually comes from boring, consistent habits, the kind you can do on a random Tuesday.

Nutrition research on post-meal cardiometabolic health often points to the same themes: meal composition matters, and so does what you do after eating. A classic cardiology review on dietary strategies also discusses how post-meal spikes in glucose and lipids can raise oxidant stress and inflammatory responses, and how simple food choices can improve that pattern (see dietary strategies for post-prandial glucose and inflammation).

Build meals that slow the sugar rush (the easy plate formula)

Use a simple template most of the time: protein + fiber-rich carbs + healthy fat + color (non-starchy veggies or fruit).

A few real-life examples:

- Breakfast: Greek yogurt, berries, chia, and walnuts (or eggs with sautéed greens and a slice of whole-grain toast).

- Lunch: Chicken or tofu salad with beans, olive oil, and a side of fruit.

- Dinner: Salmon, roasted vegetables, and lentils or brown rice.

- Snack: Apple with peanut butter, or cottage cheese with cucumber and tomatoes.

This works because protein and fat slow stomach emptying, and fiber slows absorption. Whole grains, beans, and intact fruits tend to raise glucose more gradually than refined sweets.

Order, timing, and movement, small tweaks with big payoff

If changing recipes feels like a lot, change the order. Eating veggies and protein first, then starch, can reduce the peak for some people. Pairing carbs with protein helps for the same reason: slower absorption and a steadier insulin demand.

Movement after meals is another high-return habit. A 10 to 20-minute walk acts like a glucose “sink” because working muscles pull in glucose with less insulin. Strength training helps, too, since more muscle gives you more storage space for glycogen.

Late-night high-sugar meals can be rough because sleep quality often drops, and poor sleep can worsen next-day glucose control. Alcohol and sugary drinks are common spike triggers, partly because they’re easy to consume fast and hard to “buffer” with fiber.

If you want a plain-language set of tips you can try right away, Baylor Scott and White Health shares practical ideas like balancing meals and moving after eating (see six ways to prevent blood sugar spikes).

Conclusion

Postprandial inflammation is the body’s after-meal stress response, and it can rise when glucose swings are steep and frequent. Glucose spikes inflammation is not about blaming carbs, it’s about how fast glucose enters your blood, how hard insulin has to work, and how your vessels respond in that post-meal window.

A simple plan for this week: upgrade one repeat meal (add protein and fiber), take a short walk after that meal, and note your energy and cravings. Small, repeatable changes tend to beat strict rules.

If you have diabetes, prediabetes, or symptoms like frequent dizziness, fainting, or unexplained weight loss, talk with a clinician.The aim is to keep your days more even, your nights more restful, and your meals satisfying so you feel steady, not drowsy or reaching for snacks, with infiammation control in mind.

Gas S. is a health writer who covers metabolic health, longevity science, and functional physiology. He breaks down research into clear, usable takeaways for long-term health and recovery. His work focuses on how the body works, progress tracking, and changes you can stick with. Every article is reviewed independently for accuracy and readability.

- Medical Disclaimer: This content is for education only. It doesn’t diagnose, treat, or replace medical care from a licensed professional. Read our full Medical Disclaimer here.