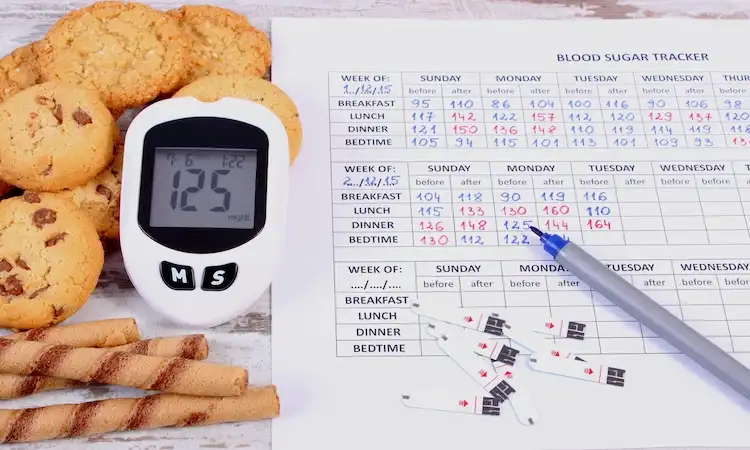

You look at your CGM graph and it’s a jagged mountain range. Or you check fingersticks for a few days and the numbers don’t “match” what you think you ate. The easy mistake is reacting to every bump, correcting too fast, changing meals daily, or blaming your willpower.

Glucose variability is simply how much, and how quickly, your glucose moves up and down. Some movement is normal. The goal isn’t a perfectly flat line. It’s steadier blood sugar, fewer surprise highs and lows, and enough predictability that you can make changes with confidence.

This article gives you a simple way to separate real patterns from random noise. It’s useful if you have diabetes, prediabetes, or you’re using a CGM for general metabolic feedback and want the data to feel less like a mood swing.

Start with the right “big picture” numbers before you zoom in

If you only study one day, you’ll end up learning that… one day was weird. Sleep, stress, a late meal, an intense workout, even a slightly different sensor day can throw things off. Patterns show up when you anchor your review to 7 to 14 days and a few stable metrics.

A practical order of operations helps:

- Look at overall stability (are you mostly in your target zone?).

- Identify repeat trouble windows (after breakfast, late afternoon, overnight).

- Only then inspect specific meals, workouts, or corrections.

Many CGM apps summarize this in an Ambulatory Glucose Profile (AGP), which is basically many days stacked into one “typical day.” If you want a clinician-style explanation of what you’re seeing, this guide on interpreting CGM data is a helpful reference.

A quick note on expectations: even people without diabetes can see bumps after meals and more day-to-day spread than they expect. A 2024 paper in Nature Medicine highlights that fasting glucose can vary within the same person across mornings when measured repeatedly with CGM, which is a reminder that not every single-point change means your health changed overnight (see CGM and intrapersonal fasting variability).

Time in range beats chasing a single daily average

Daily average glucose can look “fine” while your day is full of sharp glucose swings. That’s why many clinicians and CGM users focus on time in range, meaning how much of the day you spend in your target zone.

Here’s a simple example:

- Day A: Glucose stays mostly steady with small rises after meals.

- Day B: You spike high after lunch, crash low mid-afternoon, then rebound high at dinner.

Both days can average out to a similar number. But Day B feels worse, often leads to extra corrections or snacking, and carries more risk if lows are involved. Time in range captures that difference without you having to “eyeball” it.

Targets vary by person (and by life stage, like pregnancy), and they should match what your clinician recommends. If you want the clinical context for how time in range is used alongside other CGM metrics, the review Clinical Application of Time in Range and Other Metrics lays it out clearly.

A quick way to spot high variability without doing math

You don’t need a spreadsheet to get value from your CGM or fingersticks. Use a fast visual scan for these three signs:

First, sharp peaks and fast drops. Think “cliffs,” not “hills.” A gentle rise after eating is common. A rocket up and elevator down, especially when it repeats, often points to something actionable.

Second, big gaps between pre-meal and about 2 hours after. You don’t need to obsess over the clock. The point is to compare similar windows: before you eat, then later when digestion has had time to show its effect.

Third, rollercoasters at the same time of day. If your graph looks calm most of the day but goes wild after breakfast, that’s a pattern worth your attention.

In AGP and daily overlay views, watch the “band” around the typical curve. A wider band means your days don’t agree with each other, which often means higher glucose variability. A narrow band suggests your routine is producing consistent results (even if the results aren’t perfect yet).

How to read glucose trend patterns (and ignore the noise)

Reading glucose data well is less about being smart and more about being consistent. Ask the same questions, in the same time windows, across enough days.

A good glucose trend analysis routine looks like this:

- Pick one “zoom level” (whole day, post-meal, overnight).

- Use the same comparison points (breakfast to lunch, dinner to bedtime).

- Keep notes on context (sleep, stress, workouts, alcohol, illness).

- Decide what counts as a real pattern before you start “fixing” things.

The biggest trap is treating an isolated spike as a verdict. Glucose is responsive. It reacts to food, yes, but also to adrenaline, pain, poor sleep, dehydration, and even excitement. If you change three things at once, you’ll never know what mattered.

Use the 3-step pattern test: repeatable, explainable, action-ready

When you spot something suspicious, run it through this quick test. If it fails the test, it’s probably noise.

- Repeatable: Does it happen at least 3 times in a week, or on most days you do the same thing?

- Explainable: Can you connect it to a likely cause, like a certain meal, meal timing, stress, sleep, exercise, or medication timing?

- Action-ready: Is it big enough to matter, and safe to test a small change without risking lows?

This approach keeps you from “chasing” your glucose. It also builds confidence, because you’re not trying to control everything. You’re running simple experiments.

A strong experiment is small and specific. Examples:

- Keep the same breakfast, but add protein or fiber.

- Keep the same dinner, but take a 10 to 15-minute walk after.

- Keep your workout, but change the intensity or timing slightly.

Give one change 1 to 2 weeks if you can, especially if your schedule varies. Then re-check the same time window. If the pattern improves, you learned something real.

Know what can fake a spike: sensor lag, compression lows, and timing issues

CGMs are amazing tools, but they don’t measure blood directly. They read glucose in fluid under the skin. A kid-friendly way to picture it: blood glucose changes first, then the sensor catches up a few minutes later. That lag matters most during fast changes, like right after a meal, during hard exercise, or when treating a low.

CGMs can also show “lows” that aren’t real. Compression lows happen when you put pressure on the sensor (often while sleeping on it). The graph may drop fast and bounce back when you roll over. If you’ve seen this, you’re not alone, and it’s widely discussed (see this quick explainer on CGM compression lows).

Other “false alarms” include:

- A sensor that’s loose or irritated.

- New-sensor wonkiness in the first day.

- Rapid temperature shifts (hot shower, sauna, cold plunge) that can change circulation and readings.

Fingersticks have their own noise. Dirty hands (fruit, lotion), an old strip, or checking at a different point in the rise or fall can make two readings look like they disagree.

When should you double-check with a fingerstick (if you have that option)?

- Your symptoms don’t match the number.

- The CGM shows a sudden drop into a very low range.

- You see a weird isolated peak that doesn’t fit the day.

If you’re troubleshooting accuracy often, this practical rundown of common CGM hang-ups can help you rule out the basics before you assume your body is “doing something new.”

Common glucose swing patterns and what they usually point to

A pattern is just a repeated story. Once you can name the story, you can test a better ending. The key is to treat these as common explanations, not diagnosis or medical advice.

The classic post-meal spike: fast carbs, low fiber, or missing the timing

A typical post-meal pattern looks like: rise after eating, a peak, then a return toward baseline. The questions are how high it goes, how fast it climbs, and how long it stays elevated.

Common drivers include refined carbs, sugary drinks, low fiber, low protein, large portions, and eating very late. Eating quickly can also matter more than people think. When food hits fast, glucose often follows.

People also respond differently to the same meal. Studies using CGM in people without diabetes show a wide spread in post-meal responses, which helps explain why your friend’s “perfect” breakfast might spike you (see post-prandial glycemic response research).

Gentle experiments that don’t require a rigid diet:

- Add protein, healthy fats, or fiber to the same meal.

- Swap a sugary beverage for water or an unsweetened option.

- Try a smaller portion of the fastest carb on the plate.

- Slow the meal down, even by 5 minutes.

- Take a short walk after eating.

- Keep meal timing more consistent for a week.

If the spike shrinks across several repeats, you’ve found a real lever.

The “spike then crash” rollercoaster: big insulin response, over-correction, or intense workouts

A sharp rise followed by a quick fall can feel scary, especially if it ends in a low. This pattern often has one of three roots:

One, a meal that hits fast, triggers a strong insulin response, then drops you below where you started (some people call this reactive hypoglycemia).

Two, an over-correction, which can happen with insulin dosing, certain diabetes meds, or stacking corrections too close together.

Three, activity effects. Hard workouts can push glucose up during the session (stress hormones), then drop it later as muscles refill their stored fuel. The timing varies by workout type and your fitness level.

If lows are frequent or severe, that’s a clinician conversation, not a self-experiment. Your goal is safety first.

A simple detective habit helps: when you see a low, look back 2 to 4 hours. What happened earlier? A correction? A long gap between meals? A higher-intensity workout than usual? If the same meal or workout keeps leading to the same crash, you’ve got a pattern you can work with.

Also make sure you have a clear plan for treating lows that fits your care team’s guidance. Guessing in the moment often turns one low into a rebound high.

Overnight drift and morning highs: sleep, stress hormones, and late eating

Overnight data can be the easiest place to spot trends because you’re not eating. Look for three shapes:

- Steady line: often a sign your evening routine supports stable blood sugar.

- Gradual rise toward morning: common, and sometimes linked to the dawn phenomenon.

- Repeated dips: may suggest medication effects, alcohol, late activity, or sensor pressure.

The dawn phenomenon is an early-morning rise in glucose that happens when your body releases hormones that signal the liver to release glucose. It’s common in people with diabetes and can also show up in milder form in others. Mayo Clinic has a clear explanation of the dawn phenomenon and what can help.

Common contributors to overnight variability include late meals or snacks, alcohol (especially later), poor sleep, illness, and stress. When you’re sick, your glucose can run higher, and your “normal” rules may not apply.

Gentle experiments to test:

- Move dinner earlier by 1 to 2 hours for a week.

- Keep bedtime and wake time more consistent.

- Limit alcohol, or avoid it on nights you’re assessing patterns.

- Add a calmer wind-down routine (dim lights, less screen time).

- Tag illness or high-stress days in your notes so you don’t misread them.

Conclusion

Glucose data gets a lot less stressful when you stop treating every bump like an emergency. Start with the big picture, especially time in range and your overall stability across 7 to 14 days. Then use the repeatable, explainable, action-ready test so you’re responding to patterns, not noise.

Most glucose variability shows up in a few predictable places: post-meal spikes, spike-then-crash rollercoasters, and overnight drift into morning highs. Pick one small, safe experiment, run it for 1 to 2 weeks, and review the same time window again.

Loop in your clinician if you’re having frequent lows, you’re pregnant, or your meds change, and share your notes in the glucose hub. With the right approach, steadier glucose comes from a few steady habits, not being perfect.

Gas S. is a health writer who covers metabolic health, longevity science, and functional physiology. He breaks down research into clear, usable takeaways for long-term health and recovery. His work focuses on how the body works, progress tracking, and changes you can stick with. Every article is reviewed independently for accuracy and readability.

- Medical Disclaimer: This content is for education only. It doesn’t diagnose, treat, or replace medical care from a licensed professional. Read our full Medical Disclaimer here.